MOMENTUM, we are told, is something a boxer seeks to secure and keep hold of whenever they enter the ring on fight night.

However, it is just as true to say that throughout a fight fans want to see this same momentum change hands like a parcel and continue to do so until the music stops and neither fighter has anything left to give.

In a fight in which momentum is exchanged as freely as punches, the audience will be kept guessing, the ending can never be foretold, and it is nigh on impossible to look away.

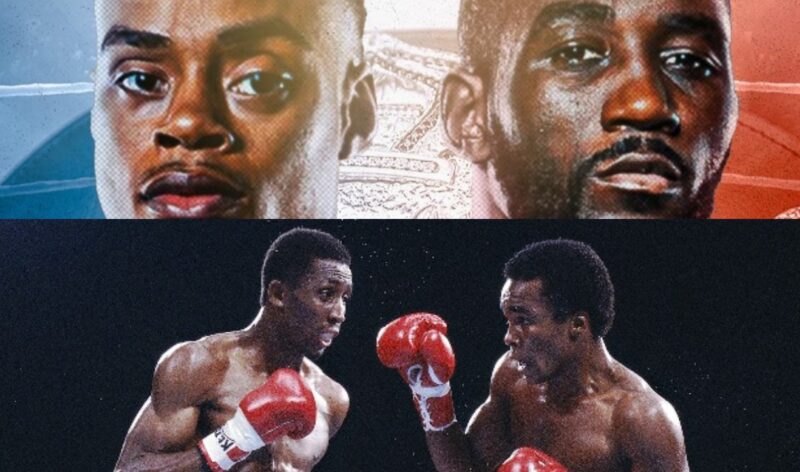

During the 1981 classic between ‘Sugar’ Ray Leonard and Thomas ‘Hitman’ Hearns, for instance, nothing was ever as it seemed and the two fighters were at their unreliable best throughout. They started as one thing and ended as something else and the fight, as a consequence, looked a certain way in round one only to then twist beyond the point of all recognition by its conclusion. This was because of momentum or, more accurately, the shifting of it from one fighter to the other. It was because both knew of multiple ways to skin an opponent.

Be that as it may, a momentum shift doesn’t necessarily have to be a by-product of action. Sometimes, as was the case with Leonard and Hearns, the momentum shifts can be signalled by a change in look – facially, or in terms of stance – or a change in a fighter’s ring position, posture, or the way they carry themselves.

It takes a special fighter, of course, to produce such moments. It takes fighters like Ray Leonard and Thomas Hearns, fighters blessed with access to various styles, looks and attributes, to add layers and dimensions to a fight in this way and defy our expectations. Their respective legacies were in fact built on this ability. Their success depended on it. Some nights they were one thing; other nights they were something else. Never, though, was either man predictable and never did they stay the same way for long.

Against each other, this capacity to adjust and surprise elevated both to a whole new level and did the same to their 1981 fight. By then, Leonard, 25, had already proven his ability to adjust his style when avenging the sole professional loss of his career against Roberto Duran in 1980.

Hearns, meanwhile, had won 32 straight (with 30 knockouts) and been spared the pain of defeat, which meant he entered his fight with Leonard both boosted and hampered by the ignorance of the undefeated fighter. He, unlike Leonard, didn’t know how it felt to lose as a pro and therefore didn’t know how to react to such a scenario. There was, as a result, little chance of him being inhibited or afraid. The only danger for a 22-year-old Hearns, in fact, was that the lessons learnt from a defeat – chiefly, the importance of change – were lessons so far taught only to Leonard, 30-1 (21).

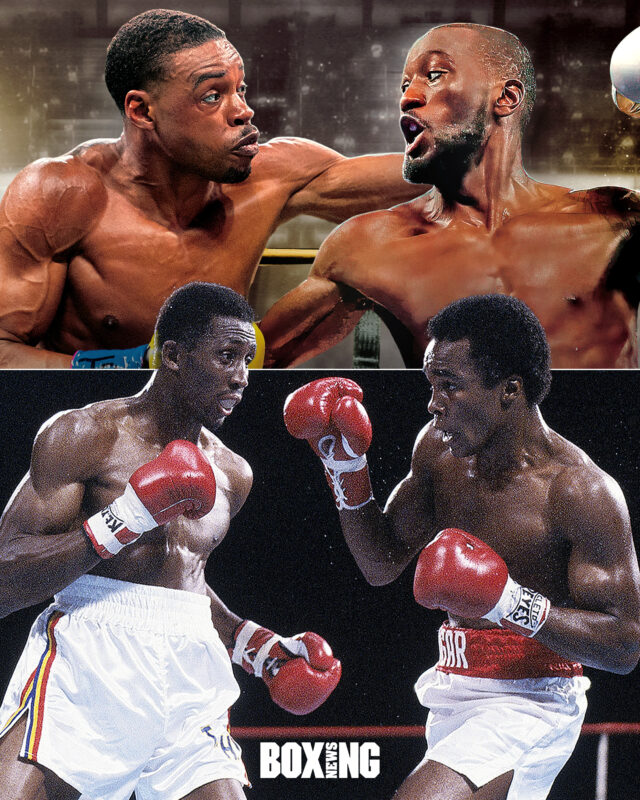

This was borne out in the first round, perhaps not at the time but certainly in hindsight. At that point, with the outdoor crowd at Caesars Palace demanding action, Hearns, the WBA champion, claimed the middle of the ring, proudly, boldly, while Leonard, the WBC champion, skated around him, reluctant to commit and often falling short whenever he did.

A lot of Leonard’s reticence owed to the pair’s physical differences: Hearns stood 6’1, with a 78-inch reach, whereas Leonard stood 5’10 with a reach of 74 inches. Yet, as well as this physical disadvantage, Leonard had to also overcome the fear of defeat, something he knew well, and the feeling of being embroiled in the wrong kind of fight, another feeling with which he was all too familiar (thanks to Duran). This alone would have been enough to have him proceed with caution. This alone would have been enough to have him wanting to be perfect.

They were nervous, too. Both of them. For no matter their ability, and irrespective of what they had achieved in the past, this was ‘The Showdown’, the fight Leonard and Hearns had been building towards for some time. It would, as an experience, change both. It would also define both. A lack of early action was therefore maybe indicative of this pressure, and both then punching after the bell, perhaps a release of nervous energy, came as no surprise, either.

Indicative of Leonard’s experience, meanwhile, not to mention his predilection for mind games, was his reaction to being cuffed after the bell by Hearns. Dipping down, wobbling to show he wasn’t hurt, Leonard reacted like a man who had been expecting to be hurt for three minutes and now, relieved that it had not happened, wanted to make it clear it had not happened.

Hearns tried again in the second round. He stalked Leonard behind his jab, accepting Leonard was unlikely to stand still, and touched Leonard from afar before landing his first right hand with a minute left in the round. It glanced rather than registered but ensured Hearns, left glove by his knee, would start introducing that punch – his pet punch – with increasing regularity. This happened as soon as the third, when Hearns, detecting Leonard was unwilling to set himself and throw anything meaningful, landed a big left hook to unsettle ‘Sugar’ Ray against the ropes. Backpedalling, Leonard now had no option but to face all he had feared: Hearns’ right hands, Hearns’ combinations, Hearns’ intensity. Against his will, the tempo had been increased and the fight had changed, with both now trading punches and places to hide in short supply.

Left with no room in which to move, Leonard bowled over a big right hand, one Hearns not only took but interpreted as a sign Leonard had finally come to play. It caused him to smile and think, Yeah, this is more like it. He then received further encouragement when Leonard stood with him in the final 30 seconds and exchanged, presenting Hearns with the opportunity to land a vicious hook to the body.

After the storm, came the quiet, however, with both champions again settling down and doing more threatening than punching and more missing than landing. It owed again to nervous energy, as well as perhaps the realisation that they were scheduled for 15 rounds, and was in the end only interrupted by sporadic moments of success: a stiff right hand from Leonard, followed by a left hook; a cross and uppercut from Hearns which landed just before the bell.

If clean punches were also conspicuous by their absence in the fifth, body language now took over, telling a story of its own. Standing taller, Hearns sensed Leonard was focused mostly on avoidance and survival and gained both confidence and momentum from this, stalking his opponent with more of a swagger, a smile on his face. He would even at one point wind up his right arm à la Leonard, though, crucially, didn’t follow through with an actual punch.

“Speed, Ray, speed!” came the call from Leonard’s corner to open the sixth and Leonard, not needing it, was already very much on the move. Eyes swollen, ideas few and far between, he was spending more time than he would have liked with his back to the ropes and more time than he would have liked on the end of Hearns’ long left jab. To find his own success, he would have to stop, slip inside the Hearns jab, and shoot his own, a feat harder to achieve in reality than it looks when written down on paper. Still, valiantly Leonard tried, firing both to the body and head, and then, after that, making his first proper breakthrough when one of his hooks wobbled Hearns and led to him stumbling back towards a corner.

It was in this corner the pair traded and it was in this corner Leonard, on the front foot for the first time, set about Hearns, now able to get inside his reach without permission; now able to get inside without Hearns realising. Nailed again by a hook, Hearns stayed on the ropes as Leonard flurried his hands, landing more rights, and continued until the bell instructed him to stop.

The sixth gave them both an incentive to continue like this: exchanging, standing in front of one another, taking risks. Leonard, in acting this way, was closing the gap between himself and Hearns and Hearns, even when hurt, had Leonard within the kind of range he had wanted him all along.

Because of this, the pattern was repeated in the seventh, with Hearns investing everything in right hands and Leonard banging him back to the body before hooking upstairs. More inclined to now gamble, knowing he could hurt Hearns, Leonard used his quicker hands inside to get Hearns unsteady again and then, once he had him on the ropes, targeted his body with his left hook. It was a clever approach. An educated approach. It had Hearns on tired legs walking back to his stool and it had Emanuel Steward, his coach, threatening to stop the fight.

As if conscious of this, Leonard returned to the middle of the ring in the eighth and went after Hearns, noticing he lacked the ability – or legs – to stay away. The roles had by this point been reversed: the boxer had become the puncher and the puncher had, begrudgingly, become the boxer. Walking in unopposed, Leonard was free to target Hearns’ body when in close and wind up a big right as the ‘Hitman’ backed up of his own volition.

All Leonard had to contend with now was the swelling around his left eye, which was quickly deteriorating, and the reality that Hearns, for all his issues, had stuck around, his legs surely destined to get stronger with the passing of time. By the ninth, in fact, with the crowd subdued and very little landing, Hearns’ improvement, both as far as movement and output, was evident for all to see. First, the strength in his legs returned, then his composure returned, then finally his confidence returned. On fresher legs, he sprung forward behind a left hook and landed it before settling down and using his height and reach to outbox Leonard for the remainder of the round.

Just as quiet was the 10th, another round vital for Hearns’ recovery; another round in which his jab was again popping and Leonard was back to finding it difficult to set and get off. By round 12, Hearns had even returned to the centre of the ring, his previous home, where he took to chucking right hands on the front foot, his posture one of both confidence and certainty.

Leonard, in contrast, now appeared puzzled, puzzled like before, and couldn’t understand why and how he had to work Hearns out all over again. He was out of ideas; his two eyes swollen. He rallied bravely in the 12th, landing an overhand right, but was then pinged immediately by a straighter right hand from Hearns as they took turns occupying the centre of the ring.

In the end, his breakthrough, the latest of a few, was as unexpected as it was dramatic. It occurred 90 seconds into round 13 when a Leonard right staggered Hearns and Hearns, having been here before, again felt his legs deceive him and again felt like a clinch was a move too difficult to accomplish. This left him susceptible to being hunted by Leonard and hurt by Leonard and, though he tried to escape and hold, Hearns was forced through the ropes due to both Leonard’s punches and the unreliability of his own limbs.

Pushed back in for more, he was then at the mercy of Leonard’s combination punching before eventually being sent to the canvas a second time, this time for a count. His head was high, snapped back above the top rope, and his body was now sliding down the ropes as though he was not so much collapsing as melting.

There was, alas, no chance of any additional shifts in momentum for the ‘Hitman’. Too tired, too hurt, and much too late, he watched helplessly as Leonard raced off his stool to begin round 14, then somehow failed to notice the windmill right hand Leonard prepared and delivered with less than a minute gone. The punch, as wild and as telegraphed as any Leonard would throw, sent Hearns spiralling once more, at which point Leonard decided to drill additional punches through his guard and bang his body with both hands. From there, a final hook to the head and a final hook to the ribs, with Hearns on the ropes, was enough to have referee Davey Pearl intervene and stop the fight at the 1.45 mark.

Leonard had done it. He had closed the gap, both in terms of distance and any scorecard deficit, he had finished on the front foot, and he had cut Hearns down to size – his size. He had also played more than one part and dabbled in more than one style, accepting that to achieve greatness was to not only beat a fellow champion at his game – Leonard’s game – but beat a fellow champion at their own game, whatever the risk involved.

by Elliot Worsell